Problem statements was the last product management tool that I wrote about. Once you’ve defined and understood the problem(s) that you’re looking to solve, the next step is to validate ways to solve the problem. As a product manager, there’s a risk of jumping straight into solutions or features, without really evaluating the best way to tackle a problem.

I learned a lot from the “Lean UX” approach to things, as introduced by Jeff Gothelf and Josh Seiden. The key point to Lean UX is the definition and validation of assumptions and hypotheses. Ultimately, this approach is all about risk management; instead of one ‘big bang’ product release, you constantly iterate and learn from actual customer usage of the product. Some people refer to this approach as the “velocity of learning.”

What are assumptions? – When thinking about problems and solutions we often make a lot of assumptions. For example, I like how Alan Klement points out that when we create user stories there’s a risk of making lots of assumptions (see below). I believe that the biggest problem isn’t so much in the assumptions themselves but more in not validating one’s assumptions before designing a product or service. What I love about the “Lean UX” approach is that it exposes assumptions early on and provides a way to validate these assumptions early and often.

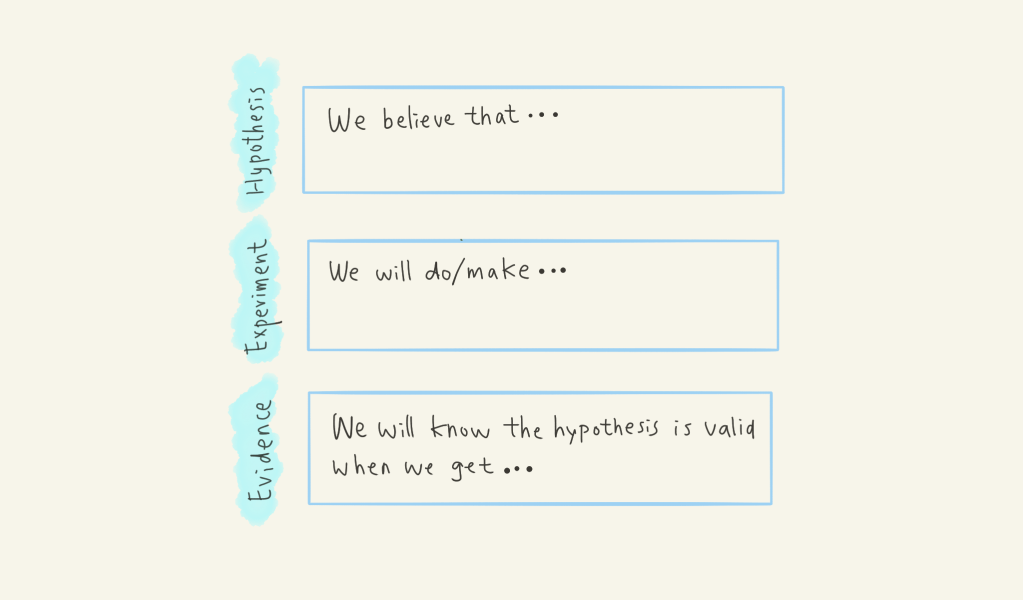

What are hypotheses? – Hypotheses are a great way to test your assumptions. A hypothesis statement is a more granular version of the original assumption and is formulated in such a way that it’s easy to test and measure specific desired outcomes:

You can use these hypotheses to test a specific product area or workflow. The key thing with assumptions and hypotheses is their focus on behavioural outcomes or changes, not just on the feature or solution in its own right.

The other important thing I learned about assumptions is to validate your riskiest assumptions first. I’ve benefited enormously from using simple prototypes to validate risky assumptions such as “this feature will definitely solve my customer’s problem” or “customers will definitely pay for this service” before committing lots of time, money and effort to solving a problem.

What assumptions and hypotheses aren’t? – I’ve seen some people falling in the trap of treating assumptions/hypotheses as absolute truths. The whole point of having assumptions and hypotheses is being transparent upfront about educated guesses, unknowns or risks.

Main learning point: Working with assumptions and hypothesis is essential in my opinion. It’s all about risk management. Instead of building something for many months before getting any customer feedback, I’d always recommend identifying and validating your riskiest assumptions first, using an iterative approach to learn ‘early and often’.

Related links for further learning:

- https://medium.com/the-job-to-be-done/replacing-the-user-story-with-the-job-story-af7cdee10c27#.7kn2clk0y

- https://marcabraham.wordpress.com/2013/04/05/book-review-lean-ux/

- https://www.uie.com/brainsparks/2014/05/21/josh-seiden-hypothesis-based-design-within-lean-ux/

- https://medium.com/@mwambach1/hypotheses-driven-ux-design-c75fbf3ce7cc#.bk8p1zvky

9 responses to “My Product Management Toolkit (5): Assumptions and Hypotheses”

[…] thing I’ve learned as a product manager is to validate a proposed product strategy or user assumptions before committing a lot of time, money and effort to a specific product […]

[…] Problem to solve – Similar to some of the questions to ask as part of point 1. above, it’s important to validate early and often whether there’s an actual problem that your product or service is solving. […]

[…] words, taking risks in such way that you learn a lot – quickly and cheaply – about your riskiest assumptions, whilst any negative ramifications are limited or […]

[…] voiced (or observed) unmet customer needs. This will in turn result in a problem statement or hypothesis to concentrate […]

[…] what you need to learn – The book covers hypotheses as an important way to figure out what it is that you want to learn through the A/B test, and to […]

[…] the assumptions that underlie each […]

[…] To be actively open-minded is to actively search for information that contradicts your pre-existing hypotheses. Such information includes the dissenting opinions of others and the careful weighing of new […]

[…] (B) – A belief is a hypothesis based on the insights generated. This isn’t a fact, but purely based on your understanding of […]

[…] insights to underpin our opinion-driven decisions made me think about starting with (loosely-held) assumptions, especially when you’re working on the first iteration of your product. You identify the […]